13 Mar International mobility Erasmus + as an antidote to the spread of the Euro-sceptic vision

“The first task in the future, without which all progress would be illusory, is the definitive abolition of the frontiers that divide Europe into sovereign states.” Thus, it was expressed, in 1941, within the Ventotene Manifesto, by Altiero Spinelli, one of the fathers of the European Union and an ideologue of the process that would have led in a few years to the establishment of the European community, as a political and economic entity.

With these assumptions, therefore, it is not surprising that the European Union has represented, for decades, a unique political laboratory: born on the ruins of the Second World War, the European project proposed the overcoming of national particularisms and the affirmation of a single supranational political entity, inspired by the values of democracy, freedom and solidarity.

The European Union, institutionally structured to represent the complexity of the needs of its communities, in its first sixty years of life managed to make a valid synthesis of this complexity that allowed it to provide adequate answers to major post-war challenges, primarily those related to the demand for democracy and the widespread needs of security, political stability and recognition of civil rights.

At the turn of the new millennium, the greatest social and economic achievements took place, such as Schengen, Maastricht and the arrival of the single currency, the Euro. Just when the process of integration seemed to have no obstacles on its way, for the European project the first difficulties emerged and, at the political level, gave rise to an ever wider contestation of its legitimacy. The financial bubble that broke out in 2008, which shocked the global market and deeply transformed the labor market, marked a watershed and put a strain on social cohesion, especially in countries where economic and social protection systems were weaker.

The current situation – from any point of view we examin it – is not very comforting. The lack of trust has now taken the upper hand: the citizens feel today more and more distant from the representative and decision-making bodies, and the European policies, which were previously perceived in a negative way, are the subject of harsh criticism and de-legitimization by euro-sceptic and sovereign political movements.

In this context, a localized phenomenon, like that of the Brexit, risks to represent a dangerous precedent for the European unity, since it has cleared in some countries the idea that the breaking of the treaties with the consequent exit from the Union could be the alone or, at the moment, the most suitable solution, among those democratically viable, for their serious internal problems. In short, a return to the past, rather than a step forward.

To avoid this drift, the European institutions are called first to rethink their policies in a deep and substantive way, to give adequate responses to the hot topics of national political agendas, with particular attention to those of countries in which the consequences of the financial crisis are heavier and more dramatic, also because of pre-existing endogenous factors of weakness: the “new” challenges that the European Union is facing and to which it must try to give adequate answers as quickly as possible, are numerous and complex, ranging from youth unemployment to climate change, from the problem of terrorism and radicalization, to the inclusion of migrant communities and the protection of personal data in the digital age.

It will not be easy to mend the rift with the citizens, who are mostly willing to trust the European project because they are still convinced of the lack of valid alternatives, but at the same time they are increasingly sceptical about the possibility that their voice can be represented in the European institutions (source Eurobarometer 2018-Democracy on the move). Although late, in 2018, in anticipation of the electoral appointment of 26 May 2019, some digital awareness campaigns were launched, with the aim of bringing citizens closer to Community policies (What Europe Does for Me) and making them more aware of their vote (This Time I’m Voting). We are waiting to see if and how much these initiatives will positively impact on the opinions of European citizens and how they will contribute to reducing the political influence of the sovereign narrative. In any case, it can be said that in Brussels, innovative political sensitization strategies were put in place to put an edge on the sovereign ‘enchantment’.

The Erasmus program, further strengthened and updated in some of its aspects, could be another effective tool for a policy capable of responding both to a growing demand for well-being (greater social and labour inclusion) but also to the demand for greater representation (greater participation in decision-making processes) which, although latent, is no less important.

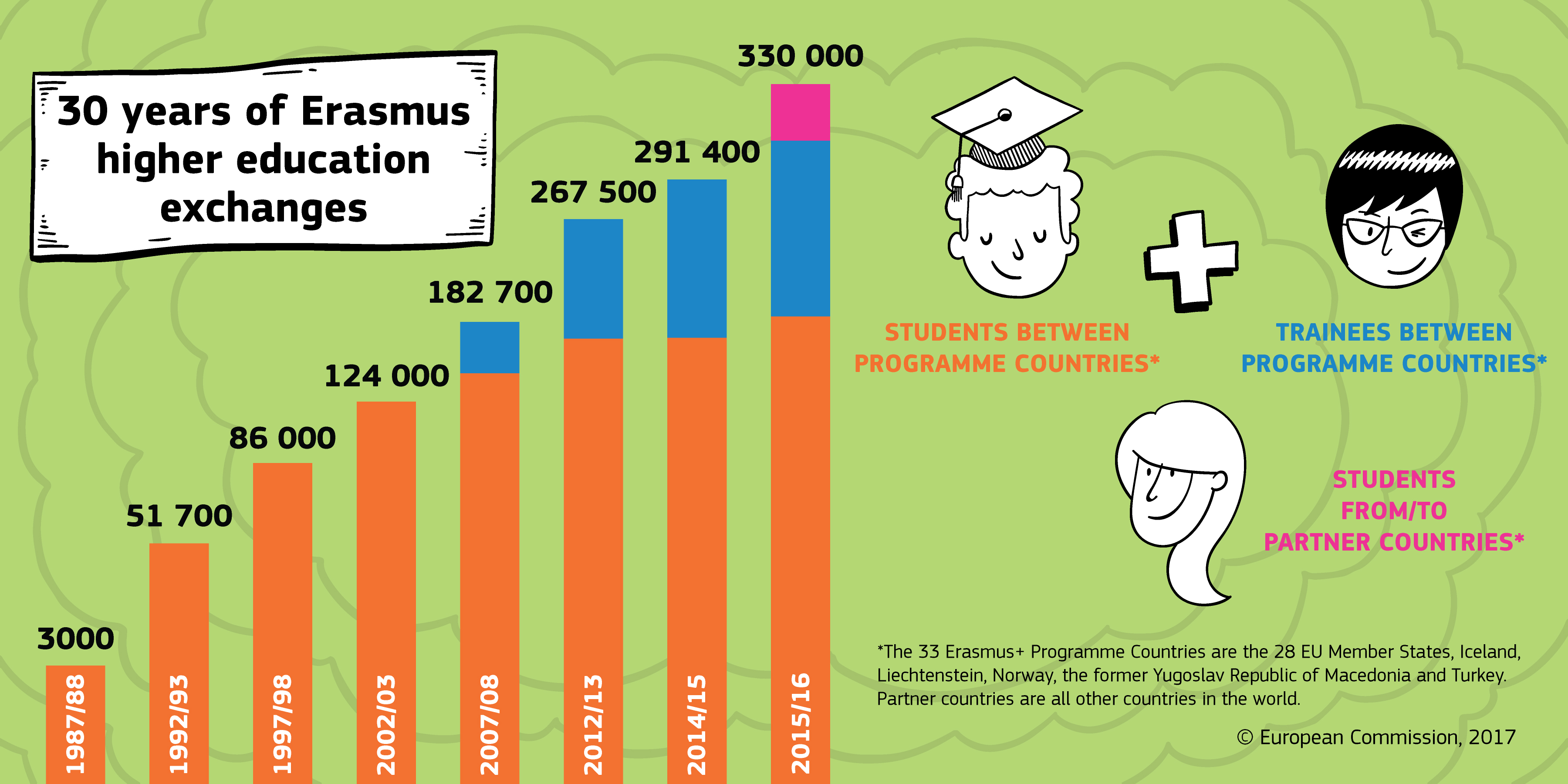

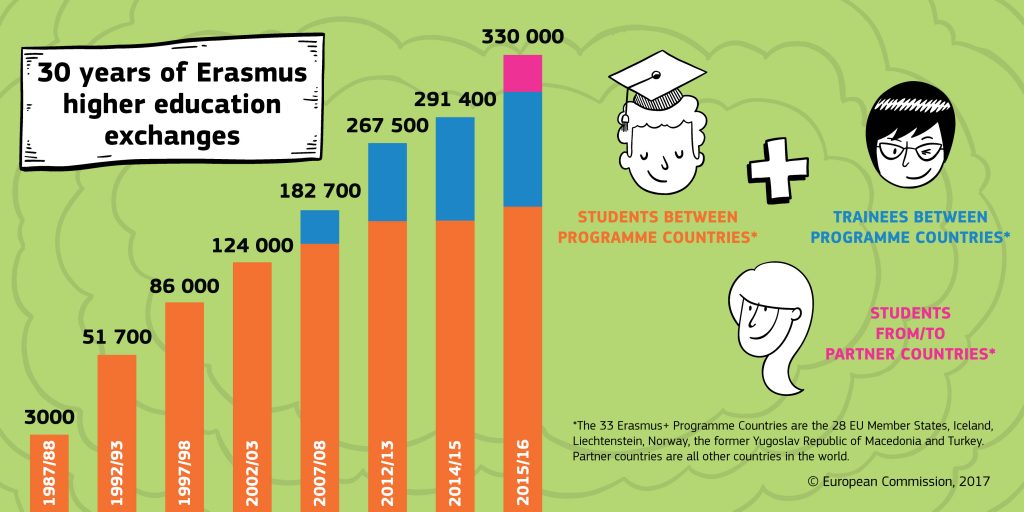

The Erasmus program was established in 1987 to allow university students to study at a European university in another country with a financial contribution to support their mobility and with the legal recognition of exams and qualifications. In its first year of implementation, the initiative involved only 3,000 students from 11 European countries on an experimental basis. I remember my Erasmus period in 1997, at Stockholm University, as the most important period of my life for the growth of my sense of European belonging.

Today, after more than thirty years, the program has added a “plus”, not only changing its name in Erasmus +, but actually aiming for a further increase in the still considerable number of applications: up to now, there were about nine millions, coming from 33 countries. Although not yet fully adequate to meet the current request for participation from all the countries of the Union, compared to the past, in fact, the program has become richer, more complex and better articulated, with several actions aimed at groups of diversified beneficiaries: high school and university students, trainees, young entrepreneurs, volunteers, academic and school staff, young people and adults in vocational training etc. The resources available (around € 15 billion) make it possible to finance not only the mobility of millions of people for study, training or voluntary work, but also several research projects and the construction of partnerships for the exchange of good practices and innovation in educational field, as well as structured dialogue initiatives with the aim of consulting young people and the social partners for their greater involvement in policy reform processes. Since 2014, a new measure has also been introduced to finance sports projects, with the aim of encouraging healthier lifestyles and combating the increase in the sedentary lifestyle of young Europeans.

With regard to the current need to further strengthen the Erasmus program, in order to make its aggregative role within the union more and more incisive, the signals that arrive from the European political institutions are considered to be encouraging. In fact, on the basis of the indications emerging from the ongoing negotiations for the approval of the future budget of the Union 2021-2027, the financial envelope for the Erasmus + program contained in the expenditure chapter reserved for social cohesion policies should in fact double – from 15 at 30 billion – compared to the previous financial framework.

This investment is justified by the results obtained to date, in particular by the positive effects on young people who took part in mobility projects during their training paths.

In general, those who take part in an Erasmus study experience abroad have at least twice the chance to find a job one year after graduation, compared to those who have never experienced such an experience. Likewise, not many know that at least one trainee out of three is offered a job by the host organization at the end of the mobility experience abroad. Surprising results, somehow replicated also in the context of professional mobility (VET).

Statistically, those who participated in the Erasmus project, if they are struggling with the problem of professional mobility, find work earlier and tend to earn an average of 25% more than those who worked exclusively in their country of origin. Even an international volunteering experience, like the Erasmus experience, can make a difference in the current job market: its presence on the curriculum is appreciated by 3/4 of the recruiter and employers (source European Commission-Education and Training Monitor EU analysis, volume 1 2018).

In the rich panorama of the Erasmus + initiatives, there is one in particular that fully exploits the training potential of mobility in terms of increasing skills and the ability to spend them in a global labour market and creates value for all the organizations involved in the initiative.

We are talking about EU4EU- European Universities for the EU. Designed and coordinated by the Italian association EuGen-European Generation, this transnational university consortium connects the higher education world with the labour market, companies, public bodies and NGO’s. The network, born in 2015, is based on a well-established planning system funded entirely by the Erasmus + Program. The network currently involves 35 universities in Spain, Italy, Croatia, to which, probably soon, will also be added French universities, and a total number of 500 host organizations between companies, public bodies and the third sector, operating in 26 European countries. In just four years, mobility projects enabled 750 students to go abroad and carry out training periods in organizations that in turn operate with European funds in the areas of training, environmental sustainability, business consulting, urban planning and scientific research. Almost 6 students out of 10 have found work at the end of the experience, bearing witness to the positive impact on their training path.

Michele D., a former Sapienza University student, is aware of this: “The experience of the internship in France in Lille allowed him to finally put into practice what he had studied, to learn a new language and above all to work. Within a team, refining his communication and problem solving skills“. Michele today works in England in the field of training and business development, and, despite the Brexit, he is proud of his choice and optimistic in his professional future.

Marta C., a foreign student, who is doing a PhD in Energy Engineering at the University of Lleida, in 2017 at the University of Perugia in three months “has had the opportunity to broaden her professional and cultural “.

The mobility experience, usually, reserves mutual benefits for the trainees and the organizations involved. Anna B., tutor in an English organization in Liverpool, reveals that “welcoming young professionals always represents an added value for the development of our organization. The hardest thing? Let them go away at the end of the mobility, so we often hire them “. This is the case of Leonardo M., a former student of the University of Padua, who last year at the end of the internship was hired and was able to continue to follow the projects in which he had been involved as a trainee.

Moreover, the universities? Since 2014, they are no longer just the departure and arrival stations of millions of students, but also active subjects of mobility. The academic and administrative staff have complemented the traditional mobility of students. University professors and staff will be able to experience periods of work or training abroad. Target? Innovate teaching, enhance the skills of teachers in designing training curricula and of administrative staff in the management of mobility projects.

To counter a closed Europe in the defence of the borders and sovereign there is a forward-looking Europe. The one made up of those who, having had work experience and study in another country, met and compared with other realities and people. That one about knowledge through the direct contact of culture and traditions of other countries is, therefore, the greatest wealth that the Erasmus project can leave to a young European, so that it is able to feel aware to be citizen of Europe, but also of the world.